Why are we not adapting to a situation that could endanger us? Why many people do not (yet) take adaptation actions to reduce the risks posed by climate change?

These are the main questions of the paper “Relationships between climate change perceptions and climate adaptation actions: policy support, information seeking, and behaviour” published on Climate Change by three researchers at the University of Groningen, Netherlands.

In a nutshell, climate change perceptions are connected to policy support, but necessarily direct action, as individual measures could appear too costly or not useful enough.

A 2022 paper on climate adaptation measures suggests that strong climate change sentiments are correlated with stronger support for policy intervention, with small to medium-sized effect sizes, but not necessarily a stronger propensity to implement climate adaptation measures.

Comparing two surveys, one in the Netherlands and one in the UK, the researchers found that people tend to implement only some of the adaptations, not all, suggesting a lack of basic knowledge and/or a lack of interest in engaging directly.

They also found out that explicitly introducing heatwaves as climate change-connected events, rather than spontaneous events, increased the strength of the relationship between climate change perceptions and policy support. Still, it did not strengthen the relationship between climate change perceptions and information-seeking intentions, nor the relationship between climate change perceptions and intentions to take preparatory adaptation measures. According to the researchers, this could be because the respondents could find the adaptation measures too costly or not useful enough.

“On the basis of protection motivation theory, we suggest that people’s perceived ability of implementing the behaviour (i.e. self-efficacy), and the perceived effectiveness of the behaviour to reduce the negative impacts of climate change (i.e. outcome efficacy; Grothmann and Patt 2005; Rogers 1983), may be relevant behaviour-specific variables that could influence the extent to which climate change perceptions are related to adaptation behaviour,” said the researchers in the paper.

The three Dutch researchers argue that it is essential to investigate general antecedents of adaptation actions, namely factors that influence different types of adaptation actions, in response to different climate-related hazards, and different contexts.

In other words, the paper suggests that perceptions are context-related, and that climate change perceptions are the leading factor explaining a deeper interest in adaptation measures.

Adaptation options in the Netherlands

The researchers list the following adaptation options to avoid pluvial flooding and heat island effects: replacing stones and concrete with plants; installing a green roof; removing stones from the sidewalk to plant plants; installing a rain barrel; installing a pond; installing sun blinds; and insulating the home.

Note: Installing rain barrels is considered to be very site-specific.

Adaptation options in the United Kingdom

The study mentioned, in the survey, three public policies to reduce the negative consequences of heatwaves: investing public money in heat warning systems in every city so that people can better protect themselves against heatwaves, investing public money in making sure there are enough air-conditioned locations publicly available during heatwaves, investing in additional health care personnel to check on vulnerable populations such as the elderly and the chronically ill during heatwaves.

The researchers listed eight preparative adaptation intentions, divided into two categories: four that people could implement inside their home, four that people could implement outside their home, or that required structural changes to the home.

Inside the home measures: putting up thermal curtains, replacing halogen or incandescent light bulbs with LED lights, applying weather strips to doors and windows to keep warm air out, and applying sun-blocking film to windows.

Four more complex measures to implement: insulating loft and walls; planting plants and trees near property; painting external roof/walls in lighter colours; installing awnings, overhangs, or other sun blinds for windows.

Note: Installing thermal curtains could work for both heat waves and extremely low temperature days.

Methodology of the study in the Netherlands

The researchers conducted an online study in a medium-sized city in the north of the Netherlands, with 3546 respondents aged 19-95 to the questionnaire. The median age was 54,5 years; 70.9% of respondents were homeowners.

The city is in the least rich municipality in the Netherlands, a country preparing for climate change due to several factors, not least the fact that most of the country is below the water levels. The city has published a heat and flood map, freely available to its citizens.

Methodology of the study in the United Kingdom

The second study in the United Kingdom, done to test the conclusions drawn in the Netherlands, had 803 participants. The questionnaire was proposed only to non-students.

The respondents in the British questionnaire were divided into two groups. Some were explained that the risks are caused by climate change (climate change condition), while others did not receive information about the cause of the risk (heatwave condition).

Participants were 803: 402 in the climate change condition and 401 in the heatwave condition. The median age was 37.8 years.

Dutch case

The paper finds that our belief in climate change, our belief that climate change is human-caused, and our belief that climate change has negative consequences are three beliefs positively correlated to their support for climate adaptation measures (correlation = 0.18, 0.16, and 0.19, respectively) in the Netherlands.

“The correlations represent a small-to-medium effect size and were very similar for the three types of climate change perceptions”, wrote the researchers in the paper, analysing which adaptation measure is then more likely.

In Groningen, for instance, people were more likely to have a green garden and a green front garden but not install sun blinds.

“We found that climate change perceptions were correlated specifically with intentions to engage in adaptation behaviours that people may more clearly perceive as ways to adapt to the risks caused by climate change, such as having a green roof or rain barrel, compared to behaviours that people may not associate with adapting to climate change risks or that people primarily adopt for other reasons, such as having a pond or sun blinds”, reads the paper published in 2022.

British case

In the British study, stronger climate change perceptions were significantly associated with stronger support for policies to reduce the impact of heat waves.

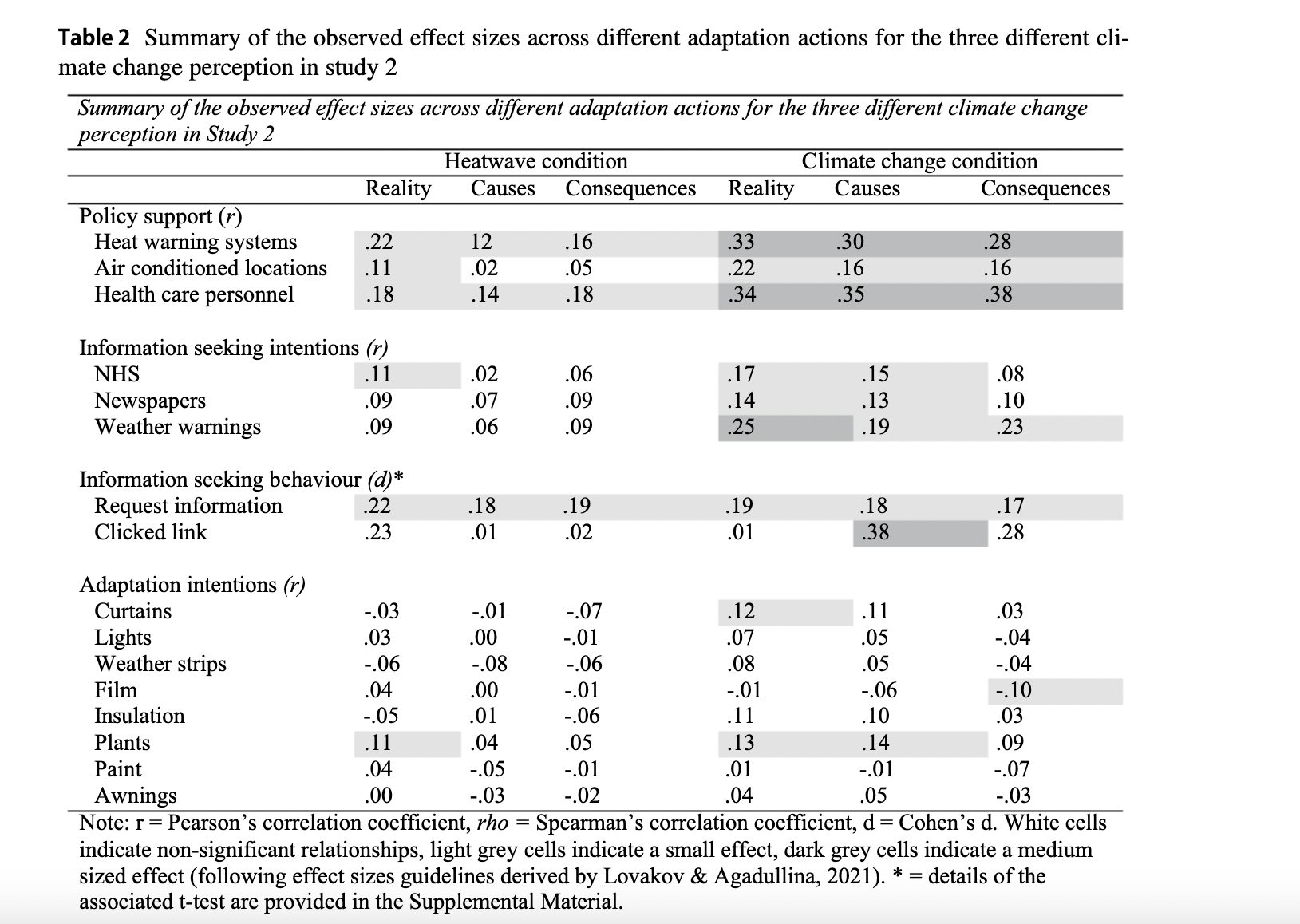

“The more people agreed that climate change was real, caused by humans, and that climate change has negative consequences, the more they supported policies to reduce the negative impacts of heatwaves, with correlation ranging from .11 to .38 across conditions, a small to

medium-large effect size”, concluded the researchers.

Additionally, correlations in the climate change condition were at least .10 stronger than in the heatwave condition (whose questionnaire did not mention climate change).

The climate change perceptions were, however, not associated with whether people clicked the link to access the information on how to react to heatwaves, with the only exception that people in the climate change condition were more likely to click the link when they more strongly believed that climate change is human-caused.

In general, climate change perceptions were not connected with preparatory adaptation intentions. “In both cases, the climate change perceptions were hardly associated with intentions to take most measures,” said the researchers in the paper, adding that “people with stronger climate change perceptions were more likely to request information on adapting to heatwaves, irrespective of the experimental condition.”

Literature review

The literature review starts by underlining that climate change perceptions are three in nature: how real climate change is, how human activity is impacting climate change, and how climate change is (negatively) impacting human life.

Before this, most papers analysed the proclivity of taking specific measures to adapt to specific consequences of climate change. But the problem is more complex than that. “Many people are facing multiple climate change risks simultaneously that require an extensive repertoire of adaptation actions: people in Colombia face increasingly more heatwaves, storms, flooding, and vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever,” said the researchers.

The literature so far did not find a consensus and a strong coherence among people, when dealing with three layers of climate change perceptions, reads the paper. For instance, people who perceive climate change as real seemed more open to climate adaptation policies, but not more likely to engage in adapting behaviours.

“The reviewed studies seem to suggest that climate change perceptions are related to policy support, but less consistently predict behavioural intentions and actual behaviours”, said the researchers in the paper. They confirmed this evidence from the literature review.

Their paper also said they were the first to relate the three different climate change perceptions with three different types of adaptation actions.

“This study was the first to comprehensively test to what extent perceptions of the reality, causes, and consequences of climate change are related to three different types of adaptation actions, namely policy support, information seeking, and preparative adaptation behaviours and intentions.”